Healing Shame

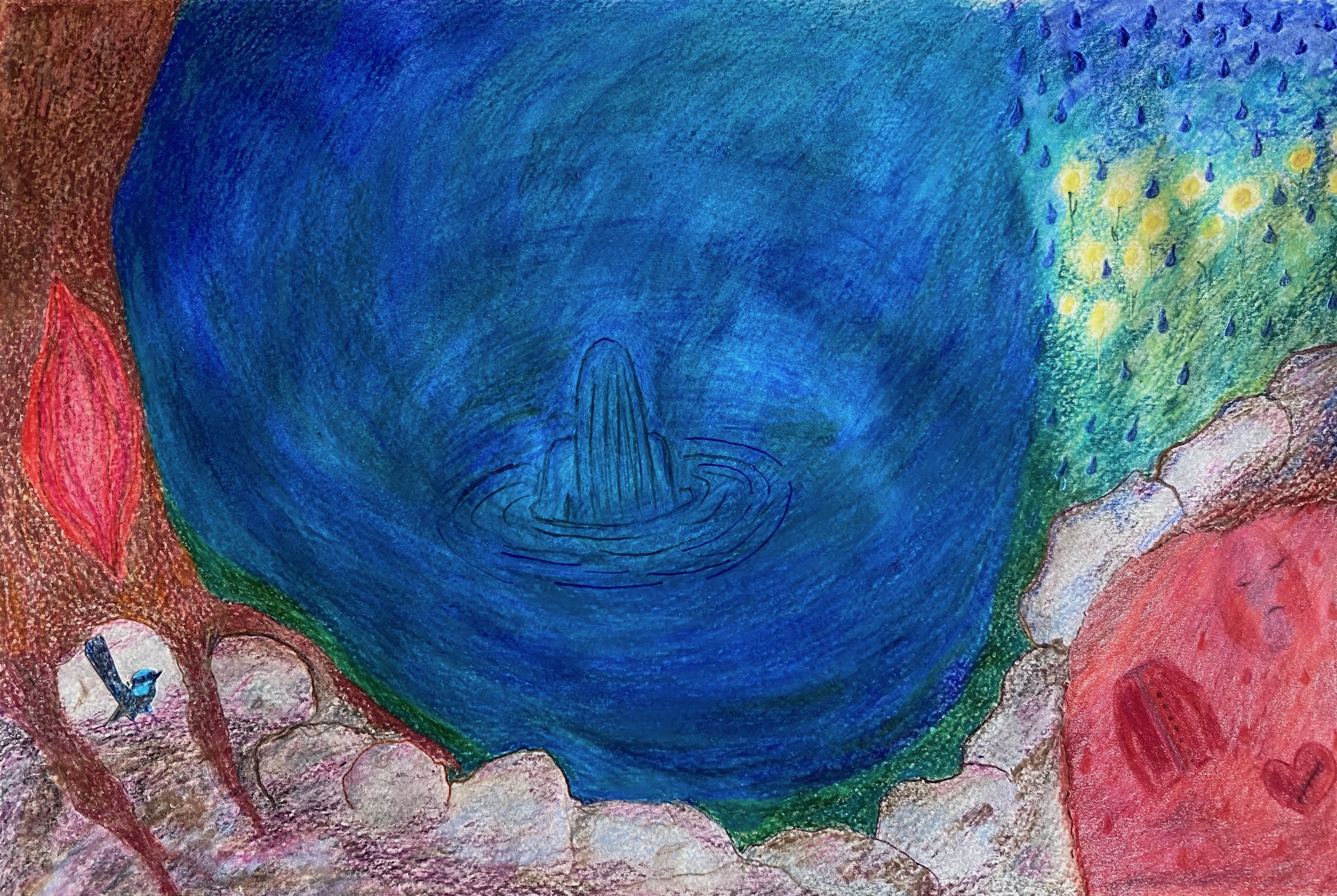

Image by Anahata Giri: Crossing the rocky threshold, from shame to renewal

Our soul holds a light to our unique way of being, of belonging, of being loved and of loving this world. This is in contrast to chronic, wound-based shame that leaves us feeling outside of belonging and cast out from love. Chronic shame usually arises from our deepest childhood wounding, where we internalise a sense not of doing wrong but of being wrong at our core. Healing from chronic shame can be a powerful step on the path of reclaiming the sovereignty of soul.

First to clarify the differences between guilt, chronic shame and what we might call present-centred shame. The emotion of guilt is an uncomfortable feeling that arises when a person recognises their own wrong-doing. Guilt comes as the message “I have done wrong.” Present-centred shame is similiar to guilt but goes deeper. It can be a very painful feeling arising from having transgressed one’s own, or culture’s, moral codes, ethics or values. Present-centred shame is usually an intensely disturbing experience as the ego struggles to comprehend the fracture of their self-image, that results from carrying out an action against his or her own ethics or values. Shame can be a powerful guide in developing conscience and morality as most of us will want to act in ways that do not bring up such a disturbing feeling.

Chronic, wound-based shame is very different from present-centred shame. Chronic shame arises not only from a perception of having done something wrong but also from a feeling of being wrong at one’s core. Internalised shame says “I am wrong.” Chronic wound-based shame usually arises in a child due to shaming behaviour from a caregiver or other adult. Shame is a common human experience and can be felt in varying degrees and circumstances. We will focus here on chronic, internalised shame that arises from childhood wounding.

As Gershen Kaufman describes in his insightful book Shame: The Power of Caring, shame can stem from childhood experience of violation, violence and developmental trauma. Shame can also arise in the absence of overt violence when there are acts of omission of care, of neglect, a repeating pattern of not attending to a child’s emotional needs. When a parent or adult in a position of authority does something harmful or demeaning to a child, children will often blame themselves. Violence and neglect cause a rupture in the relationship between the child and the parent or adult in a position of authority, such as teacher, priest and so on. It is this rupture, or, as Kaufman calls it, this broken interpersonal bridge, which results in internalised shame in the wounded child. Obviously one incident of overlooking a child’s emotional needs is unlikely to cause entrenched shame - we are talking here about a repeated pattern of harmful behaviour. This breach in the relationship is worsened if there is isolation, secrecy and no compassionate witness supporting the child. The impact of shame also increases when the shaming experience occurs in childhood and occurs at an earlier age.

When shame is internalised, the shame will sit very deeply at our core identity as a feeling of profound unworthiness. Kaufman writes that shame leaves us feeling “unspeakably and irreparably defective.” It feels unspeakable because we fear exposure, we fear others seeing how unworthy we are at our core. It feels irreparable because we feel shame as who we are. Our core identity becomes enmeshed in shame. We feel undeserving of love. Self-hatred is a close companion to shame. Shame is a barrier to self-compassion and self-love.

Internalised shame can lead to a multitude of other behaviours and feelings that attempt to suppress or address the deeply entrenched feeling of unworthiness, such as perfectionism, self-criticism, harsh self-talk, addiction, fear, depression, a loss of vitality, a desire not to live or inability to live life to its fullest, avoidance of relationships, reduced joy and so on. Tomkins (cited in Kaufman) writes “shame is felt as an inner torment, a sickness of the soul.” Shame can even be experienced as a loss of soul. In most indigenous cultures, soul loss is considered the most dangerous condition a human being could face.

Ways to Heal Shame

It is always the responsibility of the adult to make amends for their shaming behaviour and to restore trust and connection with the child. If you, dear reader, are experiencing shame that stems from childhood, you may want to read that last sentence again. In fact, I will repeat it with emphasis: it is always, always the responsibility of the adult to make amends for their shaming behaviour and the neglect or violation is never, ever the fault of the child. Where an adult is unable to make amends, a child will need the support of another trusted compassionate adult to heal shame. All too often children have nobody to turn to. Then shame may be carried into adulthood. It is never too late to heal from childhood shame. That is another sentence you may want to reread.

As Kaufman writes, central to healing shame is the repair of the broken interpersonal bridge. This repair is not likely to be undertaken with the person who broke the trust, but is much more likely to occur with another trusted person, a therapist, friend, someone who can hold space for the pain of shame with deep and compassionate listening.

Francis Weller, in his book The Wild Edge of Sorrow, writes that in order to heal shame we need to make three shifts in our understanding. The first is to move from feeling worthless, to seeing ourselves as wounded. We see the harm, neglect or violation done to us as children. We see that we are not at fault and that abusive behaviours of adults are always the responsibility of the adult. We revisit our inner child and see our innocence. We see this not merely intellectually - we understand this deeply, through our hearts, perhaps witnessed by a compassionate listener. This shift can bring up feelings of pain, sadness, grief, anger, rage and so on, as we painfully come to recognise the childhood burden of shame that was not ours to carry.

Seeing our wounding, allows the second shift, where we move from seeing ourselves through the lens of loathing and contempt to seeing ourselves with compassion. Again, we may need the support of a compassionate listener to make this shift as it involves naming the depth of our loathing, contempt, self-blame and unworthiness. A compassionate witness can help mirror back the effect of the wounding and help us see ourselves not at fault, and to see ourselves with compassion.

The third shift is moving from silence to sharing our shame and our wounding with another trusted human. Shame thrives in silence. Speaking our shame is the surest way to dissolve it. Sometimes the third shift may need to come first. Sharing our shame and our wounding with a compassionate, trusted listener, can be a powerful catalyst for reframing the worthlessness as a wound and shifting from self-contempt to self-compassion.

These are three powerful shifts in the process of recovering from shame: to shift from worthlessness to understanding our woundedness, from contempt to compassion, from silence to sharing.

Another aspect to healing from shame is to slowly create an internal holding environment of listening and compassion, by developing the inner archetype of the self-nurturing adult. Having an external compassionate listener can help us build our inner nurturing adult. We can then draw on this inner nurturing adult when the shaming thoughts and behaviours arise during the healing process. In this way we welcome back the shamed outcast parts of ourselves and reconnect with our wholeness and sense of worth.

If shame arises in my work with individuals, I honour each individual’s exquisitely unique experience of shame and help them find their unique way to tend to shame and wounding experiences. Self-designed ceremony is a powerful way to explore the unique expression and processing of shame. My drawing above summarises a self-designed ceremony of my own, described briefly here:

On a hill, I grieve and tend to my wounded child as I pace along a line of rocks, a threshold. I remember when my best friend had taken home my cardigan that I had left in the school yard. She was going to return it to me the next day. My Dad was furious that I did not have my cardigan and drove to my best friend’s house. From where I sat in the car in the street I could hear him yelling at my friend’s parents. From that day onwards I was not allowed to play with my best friend ever again…Here, now, I cross the threshold. I walk to a dam and swim in cold water, feeling cleansed. Blue Wren is a curious and trusted witness to my renewal. After my ceremony, I draw in red pencil, my burning cheeks of shame and humiliation, my wounded heart and the small red innocent cardigan. I draw myself in the birthing portal of the dam, feeling renewed and returned to my own skin.

It is beyond the scope of this short article to explore shame in its fullness and there are many nuances to shame not mentioned here. I will mention briefly that ancestral and cultural shame, are a significant part of the legacy of our modern culture of violence and oppression. In familial lineages within oppressive cultures, this ancestral shame is handed down through generations, appearing as the shame of both perpetrators and victims of: war, domestic violence, racism, sexism and all forms of oppression. In modern society, shame is part of our cultural heritage. Sometimes our shame is not simply our own, but includes our inheritance from unspoken and unprocessed wounds of the past. Can our culture hold a mature space for truth-telling and reconciliation around cultural wounding and shame? Can the three shifts described above be applied culturally, where communities shift from silence to sharing, from feelings of worthlessness to named woundedness, so we can, as a culture, shift from contempt to renewed compassion?

Lastly, James Hillman offers a powerful image from alchemy for the healing of wounds. He describes our psychological wound or issue (or shame as we have been exploring here) as like a piece of irritating grit experienced by the soft flesh of the oyster, within the confines of the shell or the psyche. We do not want to simply mask or eliminate our symptoms of wounding as then we will not recover the gift that emerges in the process of tending to our wound. Instead we listen with care and patience to what lies underneath our shame. This requires deep diving in ocean depths. We return to the piece of grit day by day, until slowly it begins to have a lustrous shine and finally the grit is transformed into a pearl. Then we can return to the world and share the gift of the pearl. The pearl of your recovery from shame is uniquely your own, but could include a robust and steady capacity to: feel whole and worthy, be self-affirming and self-loving, and to experience renewed vitality and joy in life. Understanding our own legacy of shame can also be a powerful gateway that returns us to the home of belonging in the wondrous earth community.

Anahata Giri

April 2024

References

Shame: The Power of Caring by Gershen Kaufman, Schenkman Books, 1992

The Wild Edge of Sorrow by Francis Weller, Atlantic Books, 2015

A Blue Fire: Selected Writings by James Hillman, by Thomas Moore, Harper Perennial (1997)